On the evening of a major cloud infrastructure failure, users of the high-tech sleep system from Eight Sleep found themselves in a surreal situation. Their smart beds, marketed as the ultimate in restful technology, started to act unpredictably. What was meant to be a seamless, connected experience turned chaotic. Alarms blared without reason, temperatures plummeted to freezing levels or spiked to unwelcome heat, beds got stuck in odd inclines, and in extreme cases, people ended up sleeping on the floor simply because they had no other option.

The disruption stemmed from a significant outage at Amazon Web Services (AWS). With services tied into that cloud backbone, Eight Sleep’s Pods suddenly lost connectivity, and everything dependent on that connection (control, climate, integration) shut down or misbehaved. Instead of drifting gently into slumber, some customers found themselves awake and frustrated, with devices they paid thousands of dollars for becoming unreliable overnight.

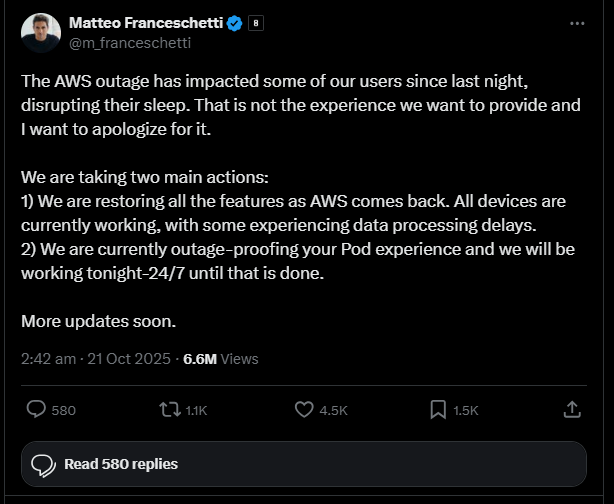

In response, the company’s CEO issued an apology and promised that engineers were working around the clock to restore service and prevent similar incidents in the future. While that acknowledgement was appreciated by some, it also raised uncomfortable questions about how much trust we place in “smart” products when they are so deeply reliant on constant connectivity.

The promise versus the reality

Eight Sleep’s Pod system is sold as a premium experience. For a high price, users get a mattress base, topper, pillows, climate-control plumbing, in-built speakers, advanced sleep-tracking, and app-based automation. Many are convinced that the investment leads to better deep sleep, more effective rest, and less waking in the night. The marketing emphasises zero-gravity rest positions, integrated sensors, and a seamless link between smartphone app and mattress.

The reality, however, is that this high-end system is also deeply dependent on the cloud and internet connectivity, especially when features like climate adjustments and app-driven profiles are involved. When the AWS outage happened, those cloud-driven components stopped working properly. Users discovered that when connectivity dropped, so did the “smart” parts of the bed. In many cases, the manual fallback simply did not exist, or at least was not intuitive. The bed essentially became dysfunctional rather than just basic.

One particularly pointed complaint noted that the associated app was using up enormous amounts of data. Some users calculated over 16 gigabytes per month just for the bed to function normally. That raised further questions about the trade-offs involved: high cost, high connectivity demand, and high risk when the cloud provider experiences problems.

What happened with Eight Sleep is much more than a quirky product malfunction. It’s a vivid illustration of a broader issue in the world of Internet of Things (IoT) devices. When everyday objects like beds, showers, fridges, or light switches are connected, they promise convenience and increased feature sets. But that connectivity also brings fragility. If the cloud link fails, the supposed “smart” object can degrade into something worse than a dumb object. It can become unpredictable, unreliable, or even unsafe.

In the case of a bed, the stakes are real. If a person’s bed cannot reliably control temperature or incline, or sensory alarms, the result isn’t just irritation. It can mean loss of sleep, increased discomfort, and a sense of betrayal at what the purchase promised. The outage shifted what was pitched as an upgrade to what felt like a hazard.

Companies building these devices are now under pressure to do more than just promise novelty. They must ensure their products can fall back to safe and predictable behaviour even if the cloud link fails. They must communicate clearly what happens when connectivity is lost—and enable offline functioning if possible. Eight Sleep’s experience shows that the line between convenience and dependency is thinner than many assumed.

What users and companies should keep in mind

For users, the first takeaway is that when devices rely heavily on remote servers and continuous internet connectivity, you are implicitly accepting a dependence on cloud infrastructure. If that provider suffers an outage, your device could become partially or wholly non-functional. Knowing that in advance can influence purchase decisions, expectations, and how you set up the device (for example, ensuring local controls exist or that WiFi stability is high).

For companies, the lesson is clear: build resilience. Relying on a single cloud service exposes you to major risk if that provider has problems. Far better architecture might include local fallback modes, edge computing options, offline user control, and redundant cloud providers. The CEO of Eight Sleep indicated that they are “outage-proofing” their product going forward, which suggests recognition of the deficiency, even if it came after user disruption.

The incident also underlines the importance of transparency. When users pay a premium for a product that sounds futuristic, they expect reliability. Clear communication about what happens in the event of an outage, what manual overrides exist, and how to proceed if the device misbehaves can mitigate frustration and build trust.

Broader implications for smart devices and consumer trust

The bed incident might seem like an odd story or a high-end fringe case, but it holds broader implications. Many more devices are becoming connected all the time, including thermostats, security cameras, home assistants, and even kitchen appliances. As our homes and daily routines increasingly tie into cloud services, we risk shifting failure points from mechanical breakdowns to internet outages and service provider disruptions.

This raises the philosophical question: Is it always better to make things smarter if the “smartness” adds failure modes rather than removing them? A conventional bed does not need a server to recline and cannot “go haywire” just because a cloud provider has downtime. With the Eight Sleep pod, ironically, some users argued the product was worse off offline than if it had never been connected.

The incident brings into focus the importance of manually accessible controls and “dumb mode” fallbacks in connected products. It also forces us to reconsider subscription models and data-heavy telemetry in smart devices. One user asked, quipping that they paid for a bed and ended up on the floor after one outage, highlighting how expectations and reality misaligned.

What began as a typical cloud disruption ended up exposing how fragile even high-end connected consumer devices can be. The smart bed that promised perfect rest instead sparked alarms, freezing modules, and user frustration. The outcomes were not minor, annoying glitches. They were a sharp reminder that connectivity is not the same as reliability, and that failure in the cloud can translate into discomfort or worse in the real world.